Mediates the control systems brand performance link

In Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements for the Degree

Doctor of Philosophyby

Douglas E. Hughes

June, 2008

_________________________________

Ed Blair

Professor of Marketing_________________________________

Eli Jones

Professor of Marketing

iii

LEVERAGING IDENTIFICATION: INFLUENCING CHANNEL SALESPERSON EFFORT AND BRAND PERFORMANCE

ABSTRACT v

LIST OF FIGURES viii

Social Identity Theory 12

Organizational Identification 14

Control System Alignment 23

Distributor Identification and Brand Identification 25

Construct Measures 38

Measurement Model 41

Cross-Level Effects and Interactions 49

DISCUSSION 51

REFERENCES 63

vii

viii

LIST OF TABLES

INTRODUCTION

Many companies utilize a distribution network of independent intermediaries, wherein the company relies on downstream channel members, e.g., brokers, agents, wholesalers, retailers, to sell its products effectively to other channel members and/or ultimately to the end-user. While in some cases the channel member serves a single supplier, more often the channel member’s product line includes products (or services) from multiple suppliers. For example, consumer products manufacturers often utilize wholesalers and/or brokers to sell to and service retailers, a wide range of industrial products are sold to companies of all sizes through distributors, and even intangible products and services are often provided through external channel entities, e.g.,

independent insurance agents. Not only do these intermediaries often represent multiple product lines, but in an era marked by consolidation at all levels of distribution

(Fontanella, 2006; Frazier, 1999), increasingly these intermediaries represent competing products within the same product category (Gale, 2005).

The challenge for the manufacturer in this environment is motivating the channel member to allocate resources on behalf of its products relative to the resources allocated in support of competitive products. Because the channel member has its own agenda that may differ from that of a particular manufacturer, the extent to which manufacturer and channel member goals, plans, and control systems are aligned will have a marked impact on what ultimately is executed in market. As a result, many channel management activities initiated by the manufacturer are directed towards influencing channel member resource allocation behavior (Anderson, Lodish, & Weitz, 1987). Manufacturers typically employ managers and representatives responsible for influencing channel member management planning, direction, and work practices on an ongoing basis. In addition, manufacturers sometimes use market power and overt initiatives to pressure

2

3

(Anderson & Oliver, 1987; Cravens, Lassk, Low, Marshall, & Moncrief, 2004a;

Jaworski, Stathakopoulos, & Krishnan, 1993), Generally speaking, formal control systems have been found to be effective in reducing role ambiguity and role conflict while increasing salesperson motivation and performance (Babakus, Cravens, Grant, Ingram, & LaForge, 1996; Baldauf, Cravens, & Piercy, 2005; Cravens et al., 2004a; Cravens, Marshall, Lassk, & Low, 2004b; Jaworski et al., 1993; Piercy, Cravens, & Morgan, 1999; Piercy, Low, & Cravens, 2004). Lurking beneath the surface however is another potential route to the channel salesperson’s mind and heart that potentially can be harnessed by both manufacturer and channel member – identification.

Still other forms of social identification are particularly relevant in a marketing environment. For example, Bhattacharya and Sen (2003) propose the concept of consumer - company identification as a vehicle for understanding consumers’

relationships with companies. When consumers incorporate defining aspects of a company’s identity into their own self-concept, they have been shown to engage in in-role and extra-role behaviors that are supportive to the company (Ahearne et al., 2005).This is in essence an extension of the fact that companies routinely attempt to forge a

While the organizational identification literature recognizes the existence of multiple foci, very few empirical studies consider issues that may occur when identification with different foci and/or with normative pressures conflict (Bartels et al., 2007; Richter, West, van Dick, & Dawson, 2006). An important distinction to be examined in this paper is the extent to which the salesperson identifies with his/her employing company (the channel member) and the extent to which the salesperson identifies with a manufacturer, or more specifically, a manufacturer’s brand, and the corresponding role of these types of identification and their interaction with channel member control systems on salesperson in-role and extra-role behaviors.

6

CONCEPTUAL BACKGROUND

Channel Influence

While manufacturers and their distribution channel intermediaries are

interdependent, challenges in coordinating activities and conflict between channel members are inevitable due to their differing perspectives and goals (e.g., Gaski, 1984; Weitz & Wang, 2004). Each entity wants to maximize its profit and the manufacturer’s brand(s) typically represent only a portion of the downstream channel member’s portfolio of products, giving rise to resource allocation issues (Anderson et al., 1987). Critical to the manufacturer is its ability to influence the channel intermediary to increase its effort on the manufacturer’s products and brands. One potential solution is to vertically integrate, and theoretical frameworks such as transaction cost analysis have been useful in examining the advantages and disadvantages of this decision (Geyskens, Steenkamp, & Kumar, 2006; Rindfleisch & Heide, 1997). Beyond vertical integration, there are three broad channel governance strategies common in vertical channels – 1) exercise of power arising from asymmetry in resources and/or dependency, 2) contractual controls, and 3) relational norms built or reinforced via communications, monitoring systems, trust, and various other influence strategies (Weitz & Wang, 2004).

9

this process is one of the critical roles played by the manufacturer rep responsible for calling on the channel member.

Reinforcement theory suggests that anticipated rewards and penalties are primary drivers of behavior (Osterhus, 1997). Assuming that the manager has exhibited consistencies with respect to the monitoring, evaluation, and outcome rewards associated with past performance plans, then the salesperson (Scott, in our example) will be prone to behave in a manner consistent with the current performance plan. In sum, all of these theories generally support the efficacy of control systems on directing salesperson effort and performance.

However, if the control systems put in place by the channel member are not aligned with the manufacturer’s goals, then the effort placed by the salesperson against the manufacturer’s brands relative to other brands is likely to be weak. Task one for the manufacturer then is working diligently to influence channel member planning.

12

act in accordance with that group membership (Hogg & Abrams, 1988; Tajfel, 1978; Tajfel & Turner, 1986; van Knippenberg & van Schie, 2000).

The sense of connection between a member and his organization is derived from two images – what the member believes is distinctive, central, and enduring about the organization (“perceived organizational identity”) and what the member believes outsiders think of the organization (“construed external image”) (Dutton & Dukerich, 1991). Other researchers have used differing terminology to refer to these same

antecedent images, e.g., “organization stereotypes” and “organization prestige” (Bergami & Bagozzi, 2000).

14

The concept of salience is important because organizational identification, like social identification in general, can involve different foci. An employee can identify with the company, division, department, work unit, and any number of other formal and informal groups that exist among the work setting. Various work-related entities to which an employee might identify can be nested or cross-cutting. Nested collectives are embedded in a hierarchical fashion within others (Ashforth & Johnson, 2001; Bagozzi, Bergami, Marzocchi, & Morandin, 2007; Ellemers & Rink, 2005). The job, workgroup, department, division, and organization are examples of nested collectives, from lower

16

What people consume, possess, and associate with contributes to their self-definitions. Consumption is central to the meaningful practice of everyday life, with product/service choices made not just on the basis of utility, but on their symbolic meanings (Wattanasuwan, 2005). An existential view is that having and being are distinct but inseparable - the self emerges from nothingness and people continually acquire things in an attempt to fill this void with meaning, symbolically creating a sense of who

18

(Fournier, 1998). Brand identity is a set of brand associations that imply a promise to consumers while helping establish a relationship from which the consumer derives functional, emotional, and self-expressive benefits (Aaker & Joachimsthaler, 2000).

There is some disagreement in the literature as to whether brand identity is created by brand strategists or co-created with stakeholders, whether it is stable or fluid, and whether it is internal or external in nature (see Csaba & Bengtsson (2006) for a good discussion).

20

might coincide with the way a consumer views himself.Clearly firms spend considerable resources attempting to build such psychological connections between their brands and consumers through advertising and other marketing communications. There is no reason to think that employees are immune to these kinds of influences and resulting attachment to the brands that their companies sell. In fact, given their higher level of involvement with the brands, and the fact that the brand’s success or failure has ramifications to the employee’s economic well-being, it is possible that the effect is even more pronounced.

We believe that these dynamics should generalize across different industries, products/services, and types of distribution channels, however, the context of our study is a 3-tier distribution system wherein a consumer products manufacturer sells its products through a wholesaler (distributor) who in turn sells to and services retail accounts in a designated territory. Irrespective of the product type, it is important to note that our focus is on the business to business exchange between manufacturer and wholesaler and between wholesaler and retailer.

22

systems (and resulting salesperson efforts) are often not completely aligned with an individual supplying manufacturer’s goals and interests (Anderson et al., 1987; Gaski, 1984; Weitz & Wang, 2004). We define Control System Alignment as the extent to which channel member control systems put in place behind a focal brand support the

manufacturer’s goals during a specified time period. Goal theory, expectancy theory, and reinforcement theory all suggest that salespeople will be motivated to expend effort in accordance with channel member control systems. Thus, when there is alignment between manufacturer goals and channel member control systems, one would expect the channel salesperson to work in accordance with manufacturer goals, i.e., to place an appropriate amount of effort behind the manufacturer’s brand.Defined as the “force, energy, or activity by which work is accomplished (Brown & Peterson, 1994), effort can also be thought of as the “vehicle by which motivation is translated into accomplished work” (Srivastava, Pelton, & Strutton, 2001). However, given a wide assortment of brands in a salesperson’s portfolio and a finite number of hours in day and a limited number of minutes in front of a buyer, the salesperson must make choices regarding what (s)he focuses on. Time spent selling one brand necessarily means less time spent selling another brand. So, expanding slightly on the definition of effort above, Brand Effort is conceptualized here as the force, energy, or activity expended against the focal brand relative to that expended against all other brands.

Distributor Identification and Brand Identification

Individuals strive for positive self-esteem, and in so doing are apt to identify with various social groups that contribute to a sense of self that is internally consistent and externally distinctive. One such social group is the organization. As discussed earlier, organizational identification can be directed towards multiple foci within the work environment, and identification with such entities can be mutually supportive or

disruptive. In this study, we examine specifically the extent to which the distributor salesperson identifies with his/her employer (Distributor Identification) and the extent to which the salesperson identifies with a focal brand (Brand Identification).The psychological connection between person and organization has often been discussed as a mechanism mediating corporate actions and stakeholder responses (Ahearne et al., 2005; Scott & Lane, 2000). One possible response on the part of an employee is an increase in effort on behalf of the organization. Since organizational identification represents the cognitive link between the definitions of the organization and the self (Porter, Steers, Mowday, & Boulian, 1974) such that perceived characteristics of the organization are integrated into the employee’s self identity, it is intuitively

26

Identification with brand and identification with distributor do not occur in a vacuum. Rather, the salesperson can identify with both brand and distributor to varying degrees, and this multiple identification can be reinforcing or diluting (Ellemers & Rink, 2005; George & Chattopadhyay, 2005; Meyer et al., 2006), particularly when viewed in the context of motivations naturally arising from the control systems instituted by the distributor. This implies the aforementioned interactions with Control System Alignment in influencing Brand Effort. Past research suggests that in nested or hierarchical forms of identification, identification with the lower level, or more proximal, entity tends to be stronger and thus more prescriptive of related outcomes than is identification with the subsuming entity. This in part is due to the greater distinctiveness provided by the lower order entity. For example, identification with one’s work group under most circumstances will be stronger or more salient than identification with the company as a whole (van Knippenberg & van Schie, 2000). Also, Ashforth and Johnson (2001) suggest that identification with lower-order collectives may generalize to upper-order collectives. However, in the circumstances examined here, there is no clear nesting relationship. On the one hand, a brand is a subset of the portfolio of brands carried by the channel member. But on the other hand,the channel member is a subset of the collection of channel members that represent the manufacturer and its brands across a broader

geography. Because of this, the relative strength and salience of identification is

ambiguous. The extent to which identification with either brand or employer is deep-structure versus situated should play a role in the outcome (Riketta et al., 2006).

H2: Higher levels of Brand Identification will (a) result in increased Brand Effort irrespective of whether control systems are aligned with the brand, and (b) strengthen the favorable impact of control system alignment on Brand Effort, while softening the negative effect on effort when control systems are not aligned with the brand.

H3: Higher levels of Distributor Identification will amplify the impact of Control System Alignment on Brand Effort, i.e., it will strengthen Brand Effort when Control System Alignment is high, and it will weaken Brand Effort when Control System Alignment is low.

Due to manufacturer pricing policies and incentives, some brands are more profitable for the retailer than others. In particular, let us assume that Pure Sound makes a considerably higher margin on its Pioneer systems and components than it does on its other brands. As a result, Pure Sound highly encourages its sales personnel to push the Pioneer brand, giving both higher quotas and more lucrative commissions in support of Pioneer stereo sales. From the perspective of Yamaha, there is low Control System alignment with Pure Sound. As a result, one would expect the relative effort expended by Pure Sound employees on behalf of Yamaha to be low. But wait – the forces of identification are at work, too.

Kymberli’s situation is unambiguous – she identifies highly with Pure Sound but not Yamaha, with the result that she follows her employer’s directives and pushes Pioneer at the expense of other brands including Yamaha. Thus, in line with goal theory and the tenets of organizational identification, her relative effort on Yamaha is weak.

31

Performance

Effort is one outcome of motivation, with performance levels varying by effort (Chonko, 1986; Churchill Jr, Ford, Hartley, & Walker Jr, 1985; Srivastava et al., 2001).

Therefore,

H4: Greater Brand Effort will result in increased Brand Sales PerformanceH5: Brand Sales Performance will interact with Control System Alignment to affect Overall Sales Performance such that greater Brand Sales Performance will result in increased Overall Sales Performance only when Control System

Alignment is high.

This seems both plausible and worthy of testing. For example, it is likely that the salesperson who identifies with a particular brand, for the same self-enhancing and self-protecting reasons discussed above for OCBs, would be prone to personally consume the brand at home and in public settings, to make the brand available at parties/gatherings where appropriate, to recommend it to friends and defend it from criticism, to encourage other employees and management to focus on the brand, to confront or report colleagues

34

METHODOLOGY

Sample

Data were gathered from eighteen large sales organizations (distributors), located in metropolitan areas across the United States. The distributors represent a shared set of consumer products manufacturers operating in the same product category, and perform the function of warehousing the various manufacturers’ brands and selling them to retailers in assigned geographic areas. Among the distributor salesperson’s brand-building responsibilities are securing and increasing distribution, expanding shelf space, selling product displays, placing point-of-sale materials, selling promotions, etc. While the distributors selected for the study were largely homogeneous with respect to the primary suppliers that they represent, externalities pertaining to company and geographic differences were controlled for. In particular, we controlled for brand market share and the number of suppliers each distributor represents by including them as covariates in the analysis. The organization structure was consistent across organizations, with each salesperson reporting to a route supervisor who in turn reports to a distributor sales manager. Surveys were administered to the salespeople, route supervisors, and sales managers in each operation, and objective sales performance data were obtained from company records for outcome measures as described below.In total, survey questionnaires were delivered to 260 salespeople, 59 route supervisors, and 18 sales managers, with a response rate of 81%, 100%, and 100% respectively. The surveys were distributed to the sales force at company offices; sales personnel were asked to complete the survey at their leisure and then return the survey directly to the researcher using provided self-addressed postage-paid envelopes. Merging

Control System Alignment refers to the extent to which distributor control systems are aligned with manufacturer brand goals. To assess this construct, distributor sales managers were surveyed using a new scale, shown in Table 1, asking the managers to assess the extent to which incentives, commissions, performance plan objectives, sales meetings, and ride-withs for a designated time period (month) focused on a particular brand. This was completed for each of four brands, with the sales manager having to

38

the same time, the multi-source nature of the data minimizes the risk of common method bias.

Brand Extra Role Behavior was measured via a new 5-point Likert scale (see Table 1) that asked salespeople to rate the extent to which they engage in various brand-supportive activities that are beyond the scope of the job description but that promote the brand in some way, e.g., “I serve this brand at parties/gatherings,” “I encourage other employees to focus their efforts on this brand,” “I correct out of stock situations, pull up facings, rebuild displays, place POS, etc. in retail accounts on personal time for this brand, e.g., when shopping while off work.”

Brand Sales Performance is an objective measured gleaned from distributor sales reports that assesses the proportion of the salesperson’s total monthly volume that is accounted for by the brand. In other words, it is defined as the percentage of sales that the focal brand represents out of the total sales volume produced by the salesperson for the time period of interest in the study – in this case a specific month, and thus can be considered a brand’s “share of total sales” for each salesperson. A similar approach has been used to assess constructs such as share of customer or share of wallet (Ahearne, Jelinek, & Jones, 2007). As discussed earlier, this is an important measure from the perspective of the manufacturer as it indicates the relative performance of its brand versus that of other brands sold by the salesperson.

Factor loadings for all constructs ranged from .66 to .91 with no unusually high cross-loadings. Reliabilities for each scale were calculated and deemed acceptable (all above .86 - see Table 2).

41

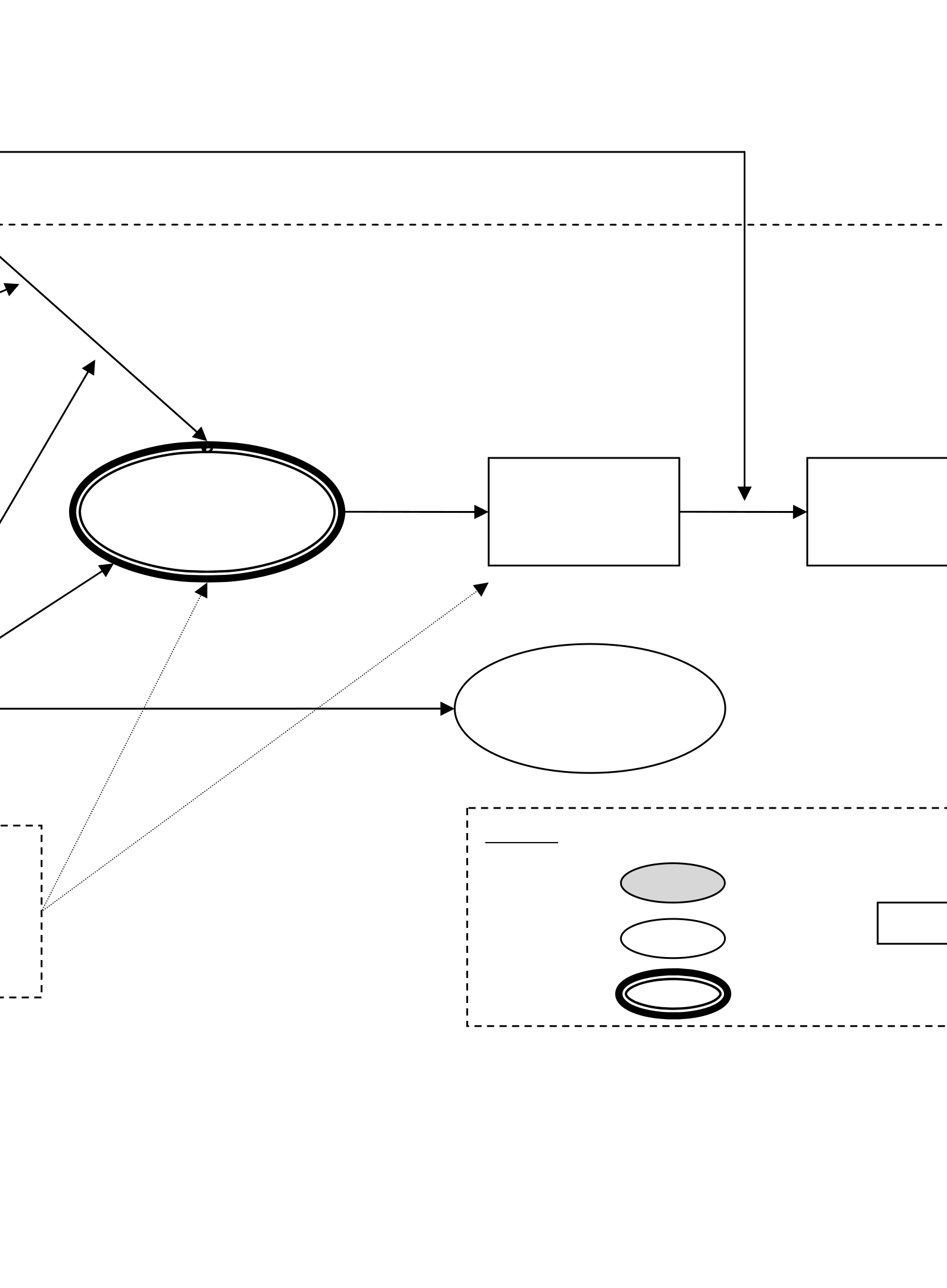

As depicted in Figure 1, three of the hypothesized relationships reside within level 1 and thus can be represented as simple linear regressions, i.e.,

(1) Brand Effort → Brand Sales Performance

BP = β0 + β1RE + r

(2) Brand ID → Brand Extra Role Support

BrdERS = β0 + β1BI + r

(3) Brand ID → Brand Usage

BrdUse = β0 + β1BI + rOutcome variable Overall Sales Performance, however, is a function of not only Brand Sales Performance but of level 2 variable Control System Alignment. Here the analysis can be thought of as including two steps, although the MPlus two-level modeling

where CSj represents the Control System Alignment for cluster j. Thus, these two equations capture the variation present at level two.

Combining the two sets of equations yields the following:

OPij = γ00 + γ01CSj + u0j + (γ10 + γ11CSj + u1j)(BPij) + rij

= γ00 + γ01CSj + γ10(BPij) + γ11CSj(BPij) + u0j + u1j(BPij) + rij Thus, the effects of Control System Alignment, Brand Performance, and the cross-level interaction of Control Systems Alignment and Brand Performance on Overall Sales Performance are captured by γ01 , γ10, and γ11 respectively.

β 1j = γ10 + γ11CSj + u1j

β 2j = γ20 + γ21CSj + u1j

46

only model (5948 lower AIC, 5966 lower BIC for the less restricted model). This improved model reflects positive relationships between Control System Alignment and Brand Effort (β = .45, p <.05), Brand Identification and Brand Effort (β = .17, p <.05), and between Brand Effort and Brand Performance (β = .34, p <.05), fulfilling additional requirements for a mediated structure, i.e., significant antecedent – final outcome and mediator –final outcome relationships (Baron & Kenny, 1986) .

The positive relationship between Brand Effort and Brand Performance

substantiates H4. The significant positive interaction between Control System Alignment and Brand Performance, combined with the negative relationship between Brand Performance and Overall Sales Performance lends support to H5, which posits that Overall Sales Performance will result from strong Brand Performance only when Control System Alignment is high.Finally, H6 pertains to another favorable outcome predicted to be positively associated with Brand Identification – the performance of brand-specific extra-role behaviors that over time potentially could enhance the brand’s viability in the

marketplace. Consistent with H6, Brand Identification was positively related to both the personal use of the brand (Brand Usage) and the exhibiting of various non-usage oriented extra-role behaviors (Extra-Role Brand Support).

49

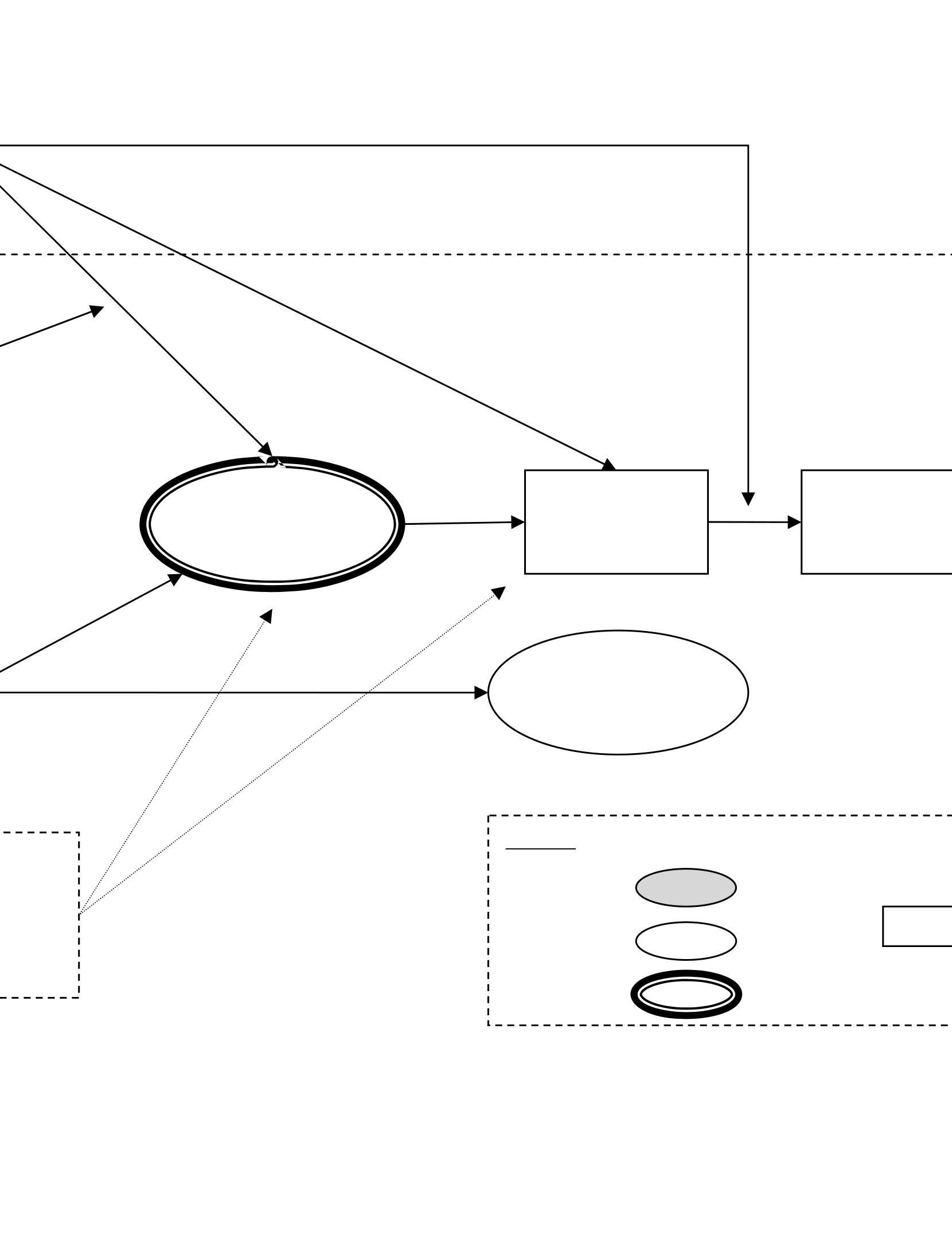

particular brand, then the salesperson who identifies with the distributor falls in line with the dictates of the distributor and expends effort against the brand. If, however, control systems are directing efforts elsewhere, the salesperson lessens effort on the brand, choosing instead to expend effort elsewhere in accordance with the controls. Since the slope of the high Distributor Identification line is steeper than the low Distributor Identification line, another interpretation is that control systems’ positive influence on salesperson brand effort is stronger when the salesperson identifies with the distributor.

Our study makes a number of contributions to both theory and practice in this regard.

First, to our knowledge we are the first to explore the forces of organizational

organizational setting – the extent to which a salesperson identifies with his/her company, and the extent to which the salesperson identifies with a supplier’s brand. Whether these forces support or conflict with one another depend on the nature of a third variable, control systems. When control systems support the brand, then brand identification and distributor identification work in concert to further strengthen brand effort. However, when control systems do not support the brand, these two forms of identification are at odds with one another. The salesperson is motivated to act in a manner consistent with the interests of the entity to which he or she identifies, but brand identification is

prompting action in favor of the brand, while distributor identification is urging the salesperson to expend efforts in a different direction.These findings reinforce, for the downstream company, the value of engendering high levels of organizational identification, since salespeople who identify with the company more closely follow the dictates of its control systems, i.e., they more closely follow the direction of management in performing their responsibilities. On the other hand, our study suggests that downstream companies might be well served by casting a wary eye at the extent to which its salespeople identify with any particular supplier’s brand, particularly those suppliers that are less important to the channel member’s business. Such brand identification works in favor of both supplier and channel member when control systems are aligned with the brand, but when the channel member wants its sales force focused on other products, brand identification can influence salesperson effort in a direction counter to that dictated by the controls. For the supplier, high organizational identification is also a “good news – bad news” situation. When control systems are aligned with a brand, then high distributor identification has a favorable

In fact, the results of this study pave the way for many additional avenues of research. This study represents an important start, but we have only begun to scratch the surface on the idea and ramifications of conflicting forms of identification within an organizational setting, and this topic could be extended even further to consumer – brand and customer – company relationships. An examination of the resilience and salience of competing forms of identification under different conditions, along with an exploration of possible adverse consequences of identity conflict to both salesperson and company could be fruitful. Also, additional investigation within the current context of a

distribution channel, with the introduction of appropriate moderators, could shed light on related questions such as whether identification under certain conditions could serve as a complete functional substitute for controls.An important question, given this study’s demonstrated positive impact of brand identification on brand effort and performance, is what are the antecedents of brand identification across a distribution channel? In other words, what steps can a

manufacturer take to facilitate the development of brand identification among channel member salespeople? A number of potential tactics come to mind, e.g., internal marketing communication initiatives, relationship marketing efforts targeting the channel salesperson, increased direct contact between supplier reps and channel sales reps, supplier hosted orientation programs, distribution of brand-identified apparel. Moreover, suppliers likely engender (or not) brand identification among channel salespeople through the latter’s observation of other externally directed activities such as consumer

advertising, public relations coverage, and the selection and behavior of supplier

representatives. From a resource allocation perspective, future research is needed to

FIGURE 1: HYPOTHESIZED MODEL Manager Control

| Rep Brand | Rep Brand | Rep Brand | Rep Overall |

|---|---|---|---|

| Performance | Performance | ||

| Effort | |||

| Rep Brand Extra |

57

| Rep Brand | Rep Brand | Rep Brand | Rep Overall |

|---|---|---|---|

| Performance | Performance | ||

| Effort | |||

| Rep Brand Extra | |||

| Identification | Role Behaviors | ||

| Source: |

Effort

High Distrib utor ID

| Low | Control System Alignment | High |

|---|

Low Control System Alignment

59

|

Brand Effor t |

|

Using a 5-pt Likert scale with 1 being Never, 2 being Rarely, 3 being Occasionally, 4 being Frequently, and 5 being Alw ays, Sales Reps were asked to rate the the extent to which they do the

Correct out of stock situations, pull up facings, rebuild displays, place POS, etc. in retail accounts on |

| CONSTR UCT |

|

|---|---|

|

|

TABLE 3

HYPOTHESIZED AND FINAL MODEL EFFECTS

References

Aaker, David A. and Erich Joachimsthaler (2000), Brand Leadership. New York:

Journal of Marketing Research (JM R), 36 (1), 45-57.

Ahearne, Michael, C. B. Bhattacharya, and T h omas Gruen ( 2005), "A ntecedents

Salesperson Service Behavior in a Competitive Environment," Journal of

th e Academy of Marketing Science (forthcoming).

Research, 24 (1), 85-97.

Anderson, Erin and Richard L. Oliver (1987), "Perspectives on Behavior-Based

Anderson, James C. and James A. Narus (1990), "A Model of Distributor Firm and

Manufacturer Firm Working Partnerships," Journal of Marketing, 54 (1),

Deborah J. Terry, Eds. Hove: Psychology Press.

Ashforth, Blake E. and Fred Mael (1989), "Social Identity Theory and the

management control, sales territory design, salesperson performance, and

sales organizatio n effectiveness," International Journal of Research in

Morandin (2007), "Customers are Members of Organizations, Too:

Assessing Foci of Identification in a Brand Community," in Working Pape r.

distinction in social psychological research: Concep tual, strategic, and

statistical considerations," Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51

28 (2), 173-90.

Becker, Thomas E. (2005), "Potential Problems in the Statistical Control of

Bergami, Massimo and Richard P. Bagozzi (2000), "Self-categorization, affective

commitment and group self-esteem as distinct aspects of social identity in

B hattacharya, C. B. and Sankar Sen (2003), "Consumer-Company Identification: A

Framework for Understanding Consumers' Relationships with Com panies,"

Brown, Steven P. and Robert A. Peterson (1994), "The effect of effort on sale s performance and job satisfaction," Journal of Marketing, 58 (2), 70.

B urmann, Christoph and Sabrina Zeplin (2005), "Building brand commitment: A behavioural approach to internal brand management," Journal of Brand Management, 12 (4), 279-300.

C ialdini, Robert B., Richard J. Borden, Avril Thorne, Marcus Randall Walker, Stephen Freeman, and Lloyd Reynolds Sloan (1976), "Basking in Reflected Glory: Three (Football) Field Studies," Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34, 366-75.

Cravens, David W., Felicia G. Lassk, George S. Low, Greg W. Marsh all, and William C. Moncrief (2004a), "Formal and informal management control combinations in sales organizations: The impact on sale sperson

consequences," Journal of Business Research, 57 (3), 241.

D ittmar, Helga (1992), The Social Psychology of Material Possessions: To Have is

to Be. Hemel Hempstead Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Anthropology of Consumption. London: Routledge.

Dukeri ch, Janet M., Brian R. Golden, and Stephen M. Shortell (2002), "Beauty I s

Stoolmiller, and Bengt Muthen (1997), "Latent Variable Modeling of

Longitudinal and Multilevel Substance Use Data," Multivariate Be havioral

Dutton, Jane E., Janet M. Dukerich, and Celia V. Harquail (1994), "Organizational

Images and Member Identification," Administrative Science Quarterly, 39

Elleme rs, Naomi (2001), "Social identity, Commitment and Work Behavior," in

Social Identity Processes in Organizational Contexts, Michael A. Hogg and

1-41.

Elliott, Richard (1997), "Existential Consumption and Irrational Desire," Europ ean

Journal of Consumer Psychology, 13 (3), 339.

F ein, Adam J. and Sandy D. Jap (1999), "Manage Consolidation in the Distribution

Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error," Journal of

Marketing Research (JMR), 18 (1), 39-50.

Gale, Thomas B. (2005), "Shifts in Alcohol Distribution Channels," in Modern

Distribution Management.

Exchanges," Journal of International Marketing, 15 (1), 92-126.

George, Elizabeth and Prithviraj Chattopadhyay (2005), "One Foot in Each Camp:

of Management Journal, 49 (3), 519-43.

Gould, Stephen J., Franklin S. Houston, and JoNel Mundt (1997), "Failing to Try to

67

the Group to Positive and Sustainable Organisational Outcomes," Applied

H ogg, Michael A. and Deborah J. Terry (2000), "Social Identity and Self-

Categorization Processes IN Organizational Contexts," Academy of

Jackson, J.W. and E.R. Smith (1999), "Conceptualizing Social Identity: A New

Framework and Evidence for the Impact of Different Dimensions,"

Evidence," Journal of Marketing, 57 (1), 57.

Kassarj ian, Harold H. (1971), "Personality and Cons umer Behavior: A Review,"

Kesmo del, David, Deborah Ball, Douglas Belkin, Dennis K. Berman, and John R.

Wilke (2007), "Miller, Co ors To Shake Up U.S. Beer Market," Wall Street

What Employees Do," in Motivation and Work Behavior, L.W. Porter and

G.A. Bigley and R.M. Steers, Eds. B urr Ridge, IL: McGraw-Hill.

Li, Andrew and Adam B. Butler (2004), "The Effects of Participation in Go al Setting and Goal Rationales on Goal Commitment: An Exploration o f Justice Med iators," Journal of Business & Psychology, 19 (1), 37-52.

Locke, Edwin A. and Gary P. Latham (2002), "Building a Practically Usef ul Theory of Goal Setting and Task Motivation," American Psychologis t, 57 (9), 705.

M ael, Fred A. and Blake E. Ashforth (1995), "Loyal from Day One: Biodata, Organizational Identification, and Turnover among Newcomers," Personn el Psychology, 48 (2), 309-33.

M arcus, H. and P. Nurius (1986), "Possible Selves," American Psychologist, 41, 954-69.

Meyer, John P., Thomas E. Becker, and Rolf van Dick (2006), "Social identities

and commitments at work: toward an integrative model," Journal of

Mohr, Jakki J., Robert J. Fisher, and John R. Nevin (1999), "Communicating for

Better Channel Relationships," Marketing Management, 8 (2), 39-45.

LISCOMP approach to estimation of latent variable relations with a

comprehensive measurement model," Psychometrika, 60 (4), 489-503.

Hypo thesis," Journal of Management, 14 (4), 547-57.

Osterhus, Thomas L. (1997), "Pro-social consumer influence strategies: When and

Compliance," Journal of Marketing, 69 (3), 66-79.

Piercy, Nigel F., David W. Cravens, and Neil A. Morgan (1999), "Relation ships

Sales Management's Behavior- and Compensation-Based Control Strategies

in Developing Countries," Journal of International Marketing, 12 (3), 30-

among Psychiatric Technicians," Journal of Applied Psychology, 59 ( 5),

603-09.

Applications and Data Analysis Methods (Second ed.). Thousand Oaks ,

CA: Sage Publications.

Relations " Academy of Management Proceedings, E1-E6.

Richter, Andreas W., Michael A. West, Rolf van Dick, and Jeremy F. Dawson

Literature," in Commitment in Organizations: Accumulated Wisdom and

New Directions, T.E. Becker H.J. Klein, & J.P. Meyer, Ed. London:

R iketta, Michael and Rolf Van Dick (2005), "Foci of attachment in organizations:

A meta-analytic comparison of the strength and correlates of workgroup

Situated and Deep-Structure Identification," Zeitschrift fur

Personalpsychologie, 5 (3), 85-93.

Journal of Organizational Behavior, 19 (3), 217.

S artre, Jean-Paul (1943), Being and Nothingness: A Phenomenological Essay on

Review," Journal of Con sumer Research, 9 (3), 287.

Sirgy, M. Joseph and Jeffrey E. Danes (1982), "Self-Image/Product-Image

Identification: Defining Ourselves Through Work Relationships," Acade my

of Management Review, 32 (1), 9-32.

Srivast ava, Rajesh, Lou E. Pelton, and David Strutton (2001), "The Will to Win:

An Investigation of How Sales Managers Can Improve The Quantitative

379-87.

Tajfel, Henri (1978), "The Achievement of Gro up Differentiation," in

William G. Austin (Eds.). Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

72

V an Dick, Rolf, Oliver Christ, Jost Stellmacher, Ulrich Wagner, Oliver Ahlswede, Cornelia Grubba, Martin Hauptmeier, Corinna Hohfeld, Kai Moltzen, and Patrick A. Tissington (2004a), "Should I Stay or Should I Go? Explaining Turnover Intentions with Organizational Identification and Job

Satisfaction," British Journal of Management, 15 (4), 351-60.v an Dick, Rolf, Michael W. Grojean, Oliver Christ, and Jan Wieseke (2006a), "Identity and the Extra Mile: Relationships between Organizational

Identification and Organizational Citizenship Behaviour," Britis h Journal of Management, 17 (4), 283-301.

73

van Knippenberg, Daan and Naomi Ellemers (2003), "Social Identity and Group

versus organizational commitment: self-definition, social exchange, and job

attitudes," Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27 (5), 571-84.

(1999), "The Influence of Goal Orientation an d Self-Regulation Tactics on

Sales Performance: A Longtitudinal Field Test," Journal of Applied

Vroom, Victor H. (1964), The Motivation to Work. New York: Wiley.

Wallen dorf, Melanie and Eric J Arnould (1989), "My Favorite Things: A Cross-

Weitz, Barton and Qiong Wang (2004), "Vertical relationships in distributio n

channels: a marketing perspective," Antitrust Bulletin, 49 (4), 859-76.