Project Management Organizational Structures Case Study

In the early days of project management, there existed a common belief that project management had to be accompanied by organizational restructuring. Project management practitioners argued that some organizational structures, such as a matrix structure, were more conducive to good project management, while others were not quite effective. Every organizational structure comes with both advantages and disadvantages.

Today, we question whether organizational restructuring is necessary. Is it possible that project management can be implemented effectively in any organizational structure if we have a cooperative culture? Restructuring is often accompanied by a shift in authority and the balance of power. Can effective project management occur at the same time that the organization undergoes restructuring?

Quasar Communications, Inc.

Quasar Communications, Inc. (QCI), is a thirty-year-old, $350 million division of Communication Systems International, the world’s largest communications company. QCI employs about 340 people of which more than 200 are engineers. Ever since the company was founded thirty years ago, engineers have held every major position within the company, including president and vice president. The vice president for accounting and finance, for example, has an electrical engineering degree from Purdue and a master’s degree in business administration from Harvard.

QCI, up until 1996, was a traditional organization where everything flowed up and down. In 1996, QCI hired a major consulting company to come in and train all of their personnel in project management. Because of the reluctance of the line managers to accept formalized project management, QCI adopted an informal, fragmented project management structure where the project managers had lots of responsibility but very little authority. The line managers were still running the show.

In 1999, QCI had grown to a point where the majority of their business base revolved around twelve large customers and thirty to forty small customers. The time had come to create a separate line organization for project managers, where each individual could be shown a career path in the company and the company could benefit by creating a body of planners and managers dedicated to the completion of a project. The project management group was headed up by a vice president and included the following full-time personnel:

- Four individuals to handle the twelve large customers

- Five individuals for the thirty to forty small customers

- Three individuals for R&D projects

- One individual for capital equipment projects

The nine customer project managers were expected to handle two to three projects at one time if necessary. Because the customer requests usually did not come in at the same time, it was anticipated that each project manager would handle only one project at a time. The R&D and capital equipment project managers were expected to handle several projects at once.

In addition to the above personnel, the company also maintained a staff of four product managers who controlled the profitable off-the-shelf product lines. The product managers reported to the vice president of marketing and sales.

In October 1999, the vice president for project management decided to take a more active role in the problems that project managers were having and held counseling sessions for each project manager. The following major problem areas were discovered.

R&D PROJECT MANAGEMENT

Project manager: “My biggest problem is working with these diverse groups that aren’t sure what they want. My job is to develop new products that can be introduced into the marketplace. I have to work with engineering, marketing, product management, manufacturing, quality assurance, finance, and accounting. Everyone wants a detailed schedule and product cost breakdown. How can I do that when we aren’t even sure what the end-item will look like or what materials are needed? Last month I prepared a detailed schedule for the development of a new product, assuming that everything would go according to the plan. I worked with the R&D engineering group to establish what we considered to be a realistic milestone. Marketing pushed the milestone to the left because they wanted the product to be introduced into the marketplace earlier. Manufacturing then pushed the milestone to the right, claiming that they would need more time to verify the engineering specifications. Finance and accounting then pushed the milestone to the left asserting that management wanted a quicker return on investment. Now, how can I make all of the groups happy?” Vice president: “Whom do you have the biggest problems with?”

Project manager: “That’s easy—marketing! Every week marketing gets a copy of the project status report and decides whether to cancel the project. Several Large Customer Project Management times marketing has canceled projects without even discussing it with me, and I’m supposed to be the project leader.”

Vice president: “Marketing is in the best position to cancel the project because they have the inside information on the profitability, risk, return on investment, and competitive environment.”

Project manager: “The situation that we’re in now makes it impossible for the project manager to be dedicated to a project where he does not have all of the information at hand. Perhaps we should either have the R&D project managers report to someone in marketing or have the marketing group provide additional information to the project managers.”

SMALL CUSTOMER PROJECT MANAGEMENT

Project manager: “I find it virtually impossible to be dedicated to and effectively manage three projects that have priorities that are not reasonably close. My low-priority customer always suffers. And even if I try to give all of my customers equal status, I do not know how to organize myself and have effective time management on several projects.”

Project manager: “Why is it that the big projects carry all of the weight and the smaller ones suffer?”

Project manager: “Several of my projects are so small that they stay in one functional department. When that happens, the line manager feels that he is the true project manager operating in a vertical environment. On one of my projects I found that a line manager had promised the customer that additional tests would be run. This additional testing was not priced out as part of the original statement of work. On another project the line manager made certain remarks about the technical requirements of the project. The customer assumed that the line managers’s remarks reflected company policy. Our line managers don’t realize that only the project manager can make commitments (on resources) to the customer as well as on company policy. I know this can happen on large projects as well, but it is more pronounced on small projects.”

LARGE CUSTOMER PROJECT MANAGEMENT

Project manager: “Those of us who manage the large projects are also marketing personnel, and occasionally, we are the ones who bring in the work. Yet, everyone appears to be our superior. Marketing always looks down on us, and when we bring in a large contract, marketing just looks down on us as if we’re riding their coattails or as if we were just lucky. The engineering group outranks us because all managers and executives are promoted from there. Those guys never live up to commitments. Last month I sent an inflammatory memo to a line manager because of his poor response to my requests. Now, I get no support at all from him. This doesn’t happen all of the time, but when it does, it’s frustrating.”

Project manager: “On large projects, how do we, the project managers, know when the project is in trouble? How do we decide when the project will fail? Some of our large projects are total disasters and should fail, but management comes to the rescue and pulls the best resources off of the good projects to cure the ailing projects. We then end up with six marginal projects and one partial catastrophe as opposed to six excellent projects and one failure. Why don’t we just let the bad projects fail?”

Vice president: “We have to keep up our image for our customers. In most other companies, performance is sacrificed in order to meet time and cost. Here at QCI, with our professional integrity at stake, our engineers are willing to sacrifice time and cost in order to meet specifications. Several of our customers come to us because of this. Last year we had a project where, at the scheduled project termination date, engineering was able to satisfy only 75 percent of the customer’s performance specifications. The project manager showed the results to the customer, and the customer decided to change his specification requirements to agree with the product that we designed. Our engineering people thought that this was a ‘slap in the face’ and refused to sign off the engineering drawings. The problem went all the way up to the president for resolution. The final result was that the customer would give us an additional few months if we would spend our own money to try to meet the original specification. It cost us a bundle, but we did it because our integrity and professional reputation were at stake.”

CAPITAL EQUIPMENT PROJECT MANAGEMENT

Project manager: “My biggest complaint is with this new priority scheduling computer package we’re supposedly considering to install. The way I understand it, the computer program will establish priorities for all of the projects in-house, based on the feasibility study, cost-benefit analysis, and return on investment. Somehow I feel as though my projects will always be the lowest priority, and I’ll never be able to get sufficient functional resources.”

Project manager: “Every time I lay out a reasonable schedule for one of our capital equipment projects, a problem occurs in the manufacturing area and the functional employees are always pulled off of my project to assist manufacturing.

And now I have to explain to everyone why I’m behind schedule. Why am I always the one to suffer?”

The vice president carefully weighed the remarks of his project managers. Now came the difficult part. What, if anything, could the vice president do to amend the situation given the current organizational environment?

Jones and Shephard Accountants,Inc.

By 1990, Jones and Shephard Accountants, Inc. (J&S) was ranked a midsized company in size by the American Association of Accountants. In order to compete with the larger firms, J&S formed an Information Services Division designed primarily for studies and analyses. By 1995, the Information Services Division (ISD) had fifteen employees.

In 1997, the ISD purchased three minicomputers. With this increased capacity, J&S expanded its services to help satisfy the needs of outside customers. By September 1998, the internal and external work loads had increased to a point where the ISD now employed over fifty people.

The director of the division was very disappointed in the way that activities were being handled. There was no single person assigned to push through a project, and outside customers did not know who to call to get answers regarding project status. The director found that most of his time was being spent on day-to-day activities such as conflict resolution instead of strategic planning and policy formulation.

The biggest problems facing the director were the two continuous internal projects (called Project X and Project Y, for simplicity) that required month-end data collation and reporting. The director felt that these two projects were important enough to require a full-time project manager on each effort.

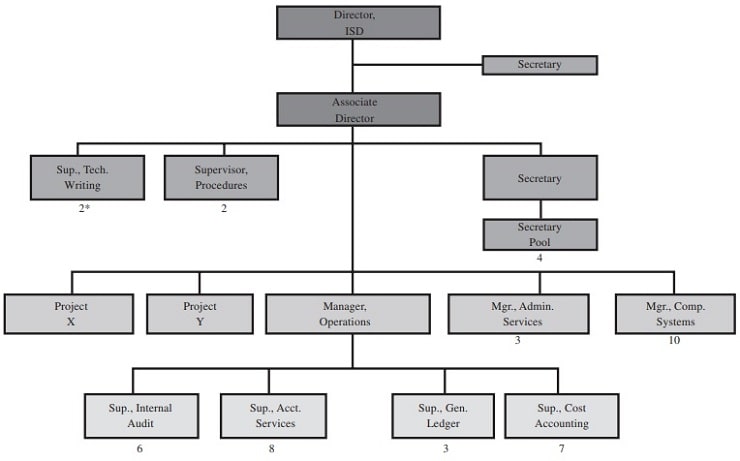

In October 1998, corporate management announced that the ISD director would be reassigned on February 1, 1999, and that the announcement of his replacement would not be made until the middle of January. The same week that the announcement was made, two individuals were hired from outside the company to take charge of Project X and Project Y. Exhibit I shows the organizational structure of the ISD.

Within the next thirty days, rumors spread throughout the organization about who would become the new director. Most people felt that the position would be filled from within the division and that the most likely candidates would be the two new project managers. In addition, the associate director was due to retire in December, thus creating two openings.

On January 3, 1999, a confidential meeting was held between the ISD director and the systems manager.

ISD director: “Corporate has approved my request to promote you to division director. Unfortunately, your job will not be an easy one. You’re going to have to restructure the organization somehow so that our employees will not have as many conflicts as they are now faced with. My secretary is typing up a confidential memo for you explaining my observations on the problems within our division.

“Remember, your promotion should be held in the strictest confidence until the final announcement later this month. I’m telling you this now so that you can

Exhibit I. ISD organizational chart

begin planning the restructuring. My memo should help you.” (See Exhibit II for the memo.)

The systems manager read the memo and, after due consideration, decided that some form of matrix would be best. To help him structure the organization properly, an outside consultant was hired to help identify the potential problems with changing over to a matrix. Six problem areas were identified by the consultant:

- The operations manager controls more than 50 percent of the people resources. You might want to break up his empire. This will have to be done very carefully.

- The secretary pool is placed too high in the organization.

- The supervisors who now report to the associate director will have to be

Exhibit II. Confidential memo

From: ISD Director

To: Systems Manager Date: January 3, 1999

Congratulations on your promotion to division director. I sincerely hope that your tenure will be productive both personally and for corporate. I have prepared a short list of the major obstacles that you will have to consider when you take over the controls.

- Both Project X and Project Y managers are highly competent individuals. In the last four or five days, however, they have appeared to create more con flicts for us than we had previously. This could be my fault for not delegating them sufficient authority, or could be a result of the fact that several of our people consider these two individuals as prime candidates for my position. In addition, the operations manager does not like other managers coming into his “empire” and giving direction.

- I’m not sure that we even need an associate director. That decision will be up to you.

- Corporate has been very displeased with our inability to work with outside You must consider this problem with any organizational structure you choose.

- The corporate strategic plan for our division contains an increased emphasis on special, internal MIS projects. Corporate wants to limit our external activities for a while until we get our internal affairs in order.

- I made the mistake of changing our organizational structure on a day-to-day Perhaps it would have been better to design a structure that could satisfy advanced needs, especially one that we can grow into.

reassigned lower in the organization if the associate director’s position is abolished.

- One of the major problem areas will be trying to convince corporate management that their change will be beneficial. You’ll have to convince them that this change can be accomplished without having to increase division manpower.

- You might wish to set up a separate department or a separate project forcustomer relations.

- Introducing your employees to the matrix will be a problem. Eachemployee will look at the change differently. Most people have the tendency of looking first at the shift in the balance of power—have I gained or have I lost power and status?

The systems manager evaluated the consultant’s comments and then prepared a list of questions to ask the consultant at their next meeting.

QUESTIONS

- What should the new organizational structure look like? Where should I puteach person, specifically the managers?

- When should I announce the new organizational change? Should it be at the same time as my appointment or at a later date?

- Should I invite any of my people to provide input to the organizational restructuring? Can this be used as a technique to ease power plays?

- Should I provide inside or outside seminars to train my people for the new organizational structure? How soon should they be held?

1 Fargo Foods

Fargo Foods is a $2 billion a year international food manufacturer with canning facilities in twenty-two countries. Fargo products include meats, poultry, fish, vegetables, vitamins, and cat and dog foods. Fargo Foods has enjoyed a 12.5 percent growth rate each of the past eight years primarily due to the low overhead rates in the foreign companies.

During the past five years, Fargo had spent a large portion of retained earnings on capital equipment projects in order to increase productivity without increasing labor. An average of three new production plants have been constructed in each of the last five years. In addition, almost every plant has undergone major modifications each year in order to increase productivity.

In 2000, the president of Fargo Foods implemented formal project management for all construction projects using a matrix. By 2004, it became obvious that the matrix was not operating effectively or efficiently. In December 2004, the author consulted for Fargo Foods by interviewing several of the key managers and a multitude of functional personnel. What follows are the several key questions and responses addressed to Fargo Foods:

- Give me an example of one of your projects.

- “The project begins with an idea. The idea can originate anywhere in the company. The planning group picks up the idea and determines the feasibility. The planning group then works ‘informally’ with the various line organizations to determine rough estimates for time and cost. The results are then fed back to the planning group and to the top management planning and steering committees. If top management decides to undertake the project, then top management selects the project manager and we’re off and running.”

- Do you have any problems with this arrangement?

- “You bet! Our executives have the tendency of equating rough estimates as detailed budgets and rough schedules as detailed schedules. Then, they want to know why the line managers won’t commit their best resources. We almost always end up with cost overruns and schedule slippages. To make matters even worse, the project managers do not appear to be dedicated to the projects. I really can’t blame them. After all, they’re not involved in planning the project, laying out the schedule, and establishing the budget. I don’t see how any project manager can become dedicated to a plan in which the project manager has no input and may not even know the assumptions or considerations that were included. Recently, some of our more experienced project managers have taken a stand on this and are virtually refusing to accept a project assignment unless they can do their own detailed planning at the beginning of the project in order to verify the constraints established by the planning group. If the project managers come up with different costs and schedules (and you know that they will), the planning group feels that they have just gotten slapped in the face. If the costs and schedules are the same, then the planning group runs upstairs to top management asserting that the project managers are wasting money by continuously wanting to replan.”

- Do you feel that replanning is necessary?

- “Definitely! The planning group begins their planning with a very crude statement of work, expecting our line managers (the true experts) to read in between the lines and fill in the details. The project managers develop a detailed statement of work and a work breakdown structure, thus minimizing the chance that anything would fall through the crack. Another reason for replanning is that the ground rules have changed between the time that the project was originally adopted by the planning group and the time that the project begins implementation. Another possibility, of course, is that technology may have changed or people can be smarter now and can perform at a higher position on the learning curve.”

- Do you have any problems with executive meddling?

- “Not during the project, but initially. Sometimes executives want to keep the end date fixed but take their time in approving the project. As a result, the project

manager may find himself a month or two behind scheduling before he even begins the project. The second problem is when the executive decides to arbitrarily change the end date milestone but keep the front end milestone fixed. On one of our projects it was necessary to complete the project in half the time. Our line managers worked like dogs to get the job done. On the next project, the same thing happened, and, once again, the line managers came to the rescue. Now, management feels that line managers cannot make good estimates and that they (the executives) can arbitrarily change the milestones on any project. I wish that they would realize what they’re doing to us. When we put forth all of our efforts on one project, then all of the other projects suffer. I don’t think our executives realize this.”

- Do you have any problems selecting good project managers and project engineers?

- “We made a terrible mistake for several years by selecting our best technical experts as the project managers. Today, our project managers are doers, not managers. The project managers do not appear to have any confidence in our line people and often try to do all of the work themselves. Functional employees are taking technical direction from the project managers and project engineers instead of the line managers. I’ve heard one functional employee say, ‘Here come those project managers again to beat me up. Why can’t they leave me alone and let me do my job?’ Our line employees now feel that this is the way that project management is supposed to work. Somehow, I don’t think so.”

- Do you have any problems with the line manager–project manager interface?

- “Our project managers are technical experts and therefore feel qualified to do all of the engineering estimates without consulting with the line managers. Sometimes this occurs because not enough time or money is allocated for proper estimating. This is understandable. But when the project managers have enough time and money and refuse to get off their ivory towers and talk to the line managers, then the line managers will always find fault with the project manager’s estimate even if it is correct. Sometimes I just can’t feel any sympathy for the project managers. There is one special case that I should mention. Many of our project managers do the estimating themselves but have courtesy enough to ask the line manager for his blessing. I’ve seen line managers who were so loaded with work that they look the estimate over for two seconds and say, ‘It looks fine to me. Let’s do it.’ Then when the cost overrun appears, the project manager gets blamed.”

- Where are your project engineers located in the organization?

- “We’re having trouble deciding that. Our project engineers are primarily responsible for coordinating the design efforts (i.e., electrical, civil, HVAC, etc).

The design manager wants these people reporting to him if they are responsible for coordinating efforts in his shop. The design manager wants control of these people even if they have their name changed to assistant project managers. The project managers, on the other hand, want the project engineers to report to them with the argument that they must be dedicated to the project and must be willing to complete the effort within time, cost, and performance. Furthermore, the project managers argue that project engineers will be more likely to get the job done within the constraints if they are not under the pressure of being evaluated by the design manager. If I were the design manager, I would be a little reluctant to let someone from outside of my shop integrate activities that utilize the resources under my control. But I guess this gets back to interpersonal skills and the attitudes of the people. I do not want to see a brick wall set up between project management and design.”

- I understand that you’ve created a new estimating group. Why was that done?

- “In the past we have had several different types of estimates such as first guess, detailed, 10 percent complete, etc. Our project managers are usually the first people at the job site and give a shoot-from-the-hip estimate. Our line managers do estimating as do some of our executives and functional employees. Because we’re in a relatively slowly changing environment, we should have well-established standards, and the estimating department can maintain uniformity in our estimating policies. Since most of our work is approved based on first-guess estimates, the question is, ‘Who should give the first-guess estimate?’ Should it be the estimator, who does not understand the processes but knows the estimating criteria, or the project engineer, who understands the processes but does not know the estimates, or the project manager, who is an expert in project management? Right now, we are not sure where to place the estimating group. The vice president of engineering has three operating groups beneath him—project management, design, and procurement. We’re contemplating putting estimating under procurement, but I’m not sure how this will work.”

- How can we resolve these problems that you’ve mentioned?

- “I wish I knew!”

Government Project Management

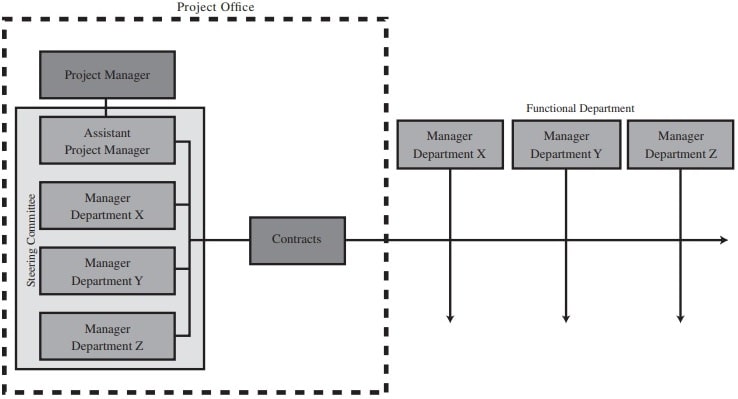

A major government agency is organized to monitor government subcontractors as shown in Exhibit I. Below are the vital characteristics of certain project office team members:

- Project manager: Directs all project activities and acts as the information focal point for the subcontractor.

- Assistant project manager: Acts as chairman of the steering committee and interfaces with both in-house functional groups and contractor.

- Department managers:Act as members of the steering committee for any projects that utilize their resources. These slots on the steering committee must be filled by the department managers themselves, not by functional employees.

- Contracts officer:Authorizes all work directed by the project office to inhouse functional groups and to the customer, and ensures that all work requested is authorized by the contract. The contracts officer acts as the focal point for all contractor cost and contractual information.

- Explain how this structure should

- Explain how this structure actually

- Can the project manager be a military type who is reassigned after a given tour of duty?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of this structure?

- Could this be used in industry?

Government Project Management Exhibit I. Project team organizational structure

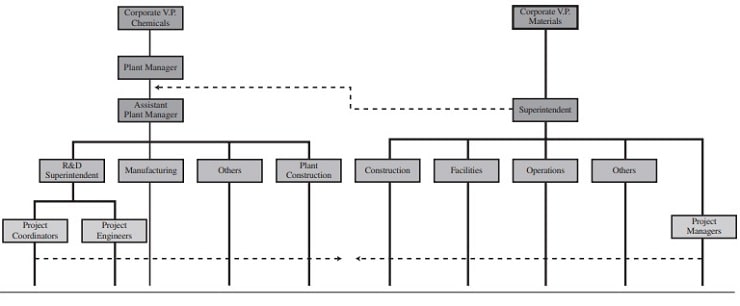

Falls Engineering

Located in New York, Falls Engineering is a $250-million chemical and materials operation employing 900 people. The plant has two distinct manufacturing product lines: industrial chemicals and computer materials. Both divisions are controlled by one plant manager, but direction, strategic planning, and priorities are established by corporate vice presidents in Chicago. Each division has its own corporate vice president, list of projects, list of priorities, and manpower control. The chemical division has been at this location for the past twenty years. The materials division is, you might say, the tenant in the landlord–tenant relationship, with the materials division manager reporting dotted to the plant manager and solid to the corporate vice president (see Exhibit I).

The chemical division employed 3,000 people in 1998. By 2003, there were only 600 employees. In 2004, the materials division was formed and located on the chemical division site with a landlord–tenant relationship. The materials division has grown from $50 million in 2000 to $120 million in 2004. Today, the materials division employs 350 people.

All projects originate in construction or engineering but usually are designed to support production. The engineering and construction departments have projects that span the entire organization directed by a project coordinator. The project coordinator is a line employee who is temporarily assigned to coordinate a project in his line organization in addition to performing his line responsibilities. Assignments are made by the division managers (who report to the plant manager)

Exhibit I. Falls Engineering organizational chart

and are based on technical expertise. The coordinators have monitoring authority only and are not noted for being good planners or negotiators. The coordinators report to their respective line managers.

Basically, a project can start in either division with the project coordinators. The coordinators draw up a large scope of work and submit it to the project engineering group, who arrange for design contractors, depending on the size of the project. Project engineering places it on their design schedule according to priority and produces prints and specifications, and receives quotes. A construction cost estimate is then produced following 60–75 percent design completion. The estimate and project papers are prepared, and the project is circulated through the plant and in Chicago for approval and authorization. Following authorization, the design is completed, and materials are ordered. Following design, the project is transferred to either of two plant construction groups for construction. The project coordinators than arrange for the work to be accomplished in their areas with minimum interference from manufacturing forces. In all cases, the coordinators act as project managers and must take the usual constraints of time, money, and performance into account.

Falls Engineering has 300 projects listed for completion between 2006 and 2008. In the last two years, less than 10 percent of the projects were completed within time, cost, and performance constraints. Line managers find it increasingly difficult to make resource commitments because crises always seem to develop, including a number of fires.

Profits are made in manufacturing, and everyone knows it. Whenever a manufacturing crisis occurs, line managers pull resources off the projects, and, of course, the projects suffer. Project coordinators are trying, but with very little success, to put some slack onto the schedules to allow for contingencies. The breakdown of the 300 plant projects is shown below:

|

Number of Projects |

$ Range |

|

120 |

less than $50,000 |

|

80 |

50,000–200,000 |

|

70 |

250,000–750,000 |

|

20 |

1–3 million |

|

10 |

4–8 million |

Corporate realized the necessity for changing the organizational structure. A meeting was set up between the plant manager, plant executives, and corporate executives to resolve these problems once and for all. The plant manager decided to survey his employees concerning their feelings about the present organizational structure. Below are their comments:

- “The projects we have the most trouble with are the small ones under $200,000. Can we use informal project management for the small ones and formal project management on the large ones?”

- Why do we persist in using computer programming to control our resources? These sophisticated packages are useless because they do not account for firefighting.”

- “Project coordinators need access to various levels of management, in both divisions.”

- “Our line managers do not realize the necessity for effective planning of resources. Resources are assigned based on emotions and not need.”

- “Sometimes a line manager gives a commitment but the project coordinator cannot force him to keep it.”

- “Line managers always find fault with project coordinators who try to develop detailed schedules themselves.”

- “If we continuously have to ‘crash’ project time, doesn’t that indicate poor planning?”

- “We need a career path in project coordination so that we can develop a body of good planners, communicators, and integrators.”

- “I’ve seen project coordinators we have no interest in the job, cannot work with diverse functional disciplines, and cannot communicate. Yet, someone assigned them as a project coordinator.”

- “Any organizational system we come up with has to be better than the one we have now.”

- “Somebody has to have total accountability. Our people are working on projects and, at the same time, do not know the project status, the current cost, the risks, and the end date.”

- “One of these days I’m going to kill an executive while he’s meddling in my project.”

- “Recently, management made changes requiring more paperwork for the project coordinators. How many hours a week do they expect me to work?”

- “I’ve yet to see any documentation describing the job description of the project coordinator.”

- “I have absolutely no knowledge about who is assigned as the project coordinator until work has to be coordinated in my group. Somehow, I’m not sure that this is the way the system should work.”

- “I know that we line managers are supposed to be flexible, but changing the priorities every week isn’t exactly my idea of fun.”

- “If the projects start out with poor planning, then management does not have the right to expect the line managers always to come to the rescue.”

- “Why is it the line managers always get blamed for schedule delays, even if it’s the result of poor planning up front?”

- “If management doesn’t want to hire additional resources, then why should the line managers be made to suffer? Perhaps we should cut out some of these useless projects. Sometimes I think management dreams up some of these projects simply to spend the allocated funds.”

- “I have yet to see a project I felt had a realistic deadline.”

After preparing alternatives and recommendations as plant manager, try to do some role playing by putting yourself in the shoes of the corporate executives. Would you, as a corporate executive, approve the recommendation? Where does profitability, sales, return on investment, and so on enter in your decision?

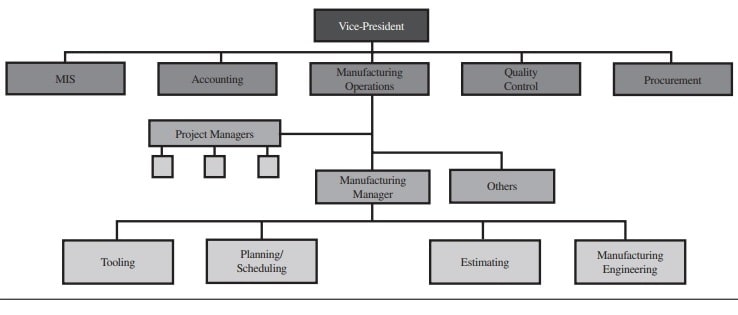

White Manufacturing

In 2004, White Manufacturing realized the necessity for project management in the manufacturing group. A three-man project management staff was formed. Although the staff was shown on the organizational chart as reporting to the manufacturing operations manager, they actually worked for the vice president and had sufficient authority to integrate work across all departments and divisions. As in the past, the vice president’s position was filled by the manufacturing operations manager. Manufacturing operations was directed by the former manufacturing manager who came from manufacturing engineering (see Exhibit I).

In 2007, the manufacturing manager created a matrix in the manufacturing department with the manufacturing engineers acting as departmental project managers. This benefited both the manufacturing manager and the group project managers since all information could be obtained from one source. Work was flowing very smoothly.

In January 2008, the manufacturing manager resigned his position effective March, and the manufacturing engineering manager began packing his bags ready to move up to the vacated position. In February, the vice president announced that the position would be filled from outside. He said also that there would be an organizational restructuring and that the three project managers would now be staff to the manufacturing manager. When the three project managers confronted the manufacturing operations manager, he said, “We’ve hired the new man in at a very high salary. In order to justify this salary, we have to give him more responsibility.”

Exhibit I. White Manufacturing organizational structure

In March 2008, the new manager took over and immediately made two declarations:

- The project managers will never go “upstairs” without first going throughhim.

- The departmental matrix will be dissolved and the department managerwill handle all of the integration.

QUESTIONS

- How do you account for the actions of the new department manager?

- What would you do if you were one of the project managers?

Martig Construction Company

Martig Construction was a family-owned mechanical subcontractor business that had grown from $5 million in 2006 to $25 million in 2008. Although the gross profit had increased sharply, the profit as a percentage of sales declined drastically. The question was, “Why the decline?” The following observations were made:

- Since Martig senior died in July of 2008, Martig junior has tried unsuccessfully to convince the family to let him sell the business. Martig junior, as company president, has taken an average of eight days of vacation per month for the past year. Although the project managers are supposed to report to Martig, they appear to be calling their own shots and are in a continuous struggle for power.

- The estimating department consists of one man, John, who estimates all jobs. Martig wins one job in seven. Once a job is won, a project manager is selected and is told that he must perform the job within the proposal estimates. Project managers are not involved in proposal estimates. They are required, however, to provide feedback to the estimator so that standards can be updated. This very seldom happens because of the struggle for power. The project managers are afraid that the estimator might be next in line for executive promotion since he is a good friend of Martig.

- The procurement function reports to Martig. Once the items are ordered,the project manager assumes procurement responsibility. Several times in the past, the project manager has been forced to spend hour after hour trying to overcome shortages or simply to track down raw materials. Most project managers estimate that approximately 35 percent of their time involves procurement.

- Site superintendents believe they are the true project managers, or at least at the same level. The superintendents are very unhappy about not being involved in the procurement function and, therefore, look for ways to annoy the project managers. It appears that the more time the project manager spends at the site, the longer the work takes; the feedback of information to the home office is also distorted.

Mohawk National Bank

“You’re really going to have your work cut out for you, Randy,” remarked Pat Coleman, vice president for operations. “It’s not going to be easy establishing a project management organizational structure on top of our traditional structure. We’re going to have to absorb the lumps and bruises and literally ‘force’ the system to work.”

BACKGROUND

Between 1988 and 1998, Mohawk National matured into one of Maine’s largest full-service banks, employing a full-time staff of some 1,200 employees. Of the 1,200 employees, approximately 700 were located in the main offices in downtown Augusta.

Mohawk matured along with other banks in the establishment of computerized information processing and decision-making. Mohawk leased the most upto-date computer equipment in order to satisfy customer demands. By 1994, almost all departments were utilizing the computer.

By 1995, the bureaucracy of the traditional management structure was creating severe administrative problems. Mohawk’s management had established many complex projects to be pursued, each one requiring the involvement of several departments. Each department manager was setting his or her own priorities for the work that had to be performed. The traditional organization was too weak structurally to handle problems that required integration across multiple departments. Work from department to department could not be tracked because there was no project manager who could act as focal point for the integration of work.

UNDERSTANDING THE CHANGEOVER PROBLEM

It was a difficult decision for Mohawk National to consider a new organizational structure, such as a matrix. Randy Gardner, director of personnel, commented on the decision:

Banks, in general, thrive on traditionalism and regimentation. When a person accepts a position in our bank, he or she understands the strict rules, policies, and procedures that have been established during the last 30 years.

We know that it’s not going to be easy. We’ve tried to anticipate the problems that we’re going to have. I’ve spent a great deal of time with our vice president of operations and two consultants trying to predict the actions of our employees.

The first major problem we see is with our department managers. In most traditional organizations, the biggest functional department emerges as the strongest. In a matrix organization, or almost any other project form for that matter, there is a shift in the balance of power. Some managers become more important in their new roles and others not so important. We think our department managers are good workers and that they will be able to adapt.

Our biggest concern is with the functional employees. Many of our functional people have been with us between twenty and thirty years. They’re seasoned veterans. You must know that they’re going to resist change. These people will fight us all the way. They won’t accept the new system until they see it work. That’ll be our biggest challenge: to convince the functional team members that the system will work.

Pat Coleman, the vice president for operations, commented on the problems that he would be facing with the new structure:

Under the new structure, all project managers will be reporting to me. To be truthful, I’m a little scared. This changeover is like a project in itself. As with any project, the beginning is the most important phase. If the project starts out on the right track, people might give it a chance. But if we have trouble, people will be quick to revert back to the old system. Our people hate change. We cannot wait one and a half to two years for people to get familiar with the new system. We have to hit them all at once and then go all out to convince them of the possibilities that can be achieved.

This presents a problem in that the first group of project managers must be highly capable individuals with the ability to motivate the functional team members. I’m still not sure whether we should promote from within or hire from the outside. Hiring from the outside may cause severe problems in that our employees like to work with people they know and trust. Outside people may not know our people. If they make a mistake and aggravate our people, the system will be doomed to failure.

Promoting from within is the only logical way to go, as long as we can find qualified personnel. I would prefer to take the qualified individuals and give them a lateral promotion to a project management position. These people would be on trial for about six months. If they perform well, they will be promoted and permanently assigned to project management. If they can’t perform or have trouble enduring the pressure, they’ll be returned to their former functional positions. I sure hope we don’t have any inter- or intramatrix power struggles.

Implementation of the new organizational form will require good communications channels. We must provide all of our people with complete and timely information. I plan on holding weekly meetings with all of the project and functional managers. Good communications channels must be established between all resource managers. These team meetings will give people a chance to see each other’s mistakes. They should be able to resolve their own problems and conflicts. I’ll be there if they need me. I do anticipate several conflicts because our functional managers are not going to be happy in the role of a support group for a project manager. That’s the balance of power problem I mentioned previously.

I have asked Randy Gardner to identify from within our ranks the four most likely individuals who would make good project managers and drive the projects to success. I expect Randy’s report to be quite positive. His report will be available next week.

Two weeks later, Randy Gardner presented his report to Pat Coleman and made the following observations:

I have interviewed the four most competent employees who would be suitable for project management. The following results were found:

Andrew Medina, department manager for cost accounting, stated that he would refuse a promotion to project management. He has been in cost accounting for twenty years and does not want to make a change into a new career field.

Larry Foster, special assistant to the vice president of commercial loans, stated that he enjoyed the people he was working with and was afraid that a new job in project management would cause him to lose his contacts with upper level management. Larry considers his present position more powerful than any project management position.

Chuck Folson, personal loan officer stated that in the fifteen years he’s been with Mohawk National, he has built up strong interpersonal ties with many members of the bank. He enjoys being an active member of the informal organization and does not believe in the applications of project management for our bank.

Jane Pauley, assistant credit manager, stated that she would like the position, but would need time to study up on project management. She feels a little unsure about herself. She’s worried about the cost of failure.

Now Pat Coleman had a problem. Should he look for other bank employees who might be suitable to staff the project management functions or should he look externally to other industries for consultants and experienced project managers?

QUESTIONS

- How do you implement change in a bank?

- What are some of the major reasons why employees do not want to become project managers?

- Should the first group of project managers be laterally assigned?

- Should the need for project management first be identified from within the organization?

- Can project management be forced upon an organization?

- Does the bank appear to understand project management?

- Should you start out with permanent or temporary project management positions?

- Should the first group of project managers be found from within the organization?

- Will people be inclined to support the matrix if they see that the project managers are promoted from within?

- Suppose that the bank goes to a matrix, but without the support of top management. Will the system fail?

- How do you feel about in-house workshops to soften the impact of project management?